Even if you're not in academia, if you read this article from the New York Times, you'll realize that academic publishing is undergoing upheaval. Essentially, it's the same upheaval that's upending publishing in general: The quality of what's disseminated would improve dramatically if it were subject to continuous revision based on feedback from as large a group of people as possible who have information to bring to bear. It's just that the established players are having a hard time understanding, let alone adopting, the new quality model.

The longstanding quality model to be replaced in academic publishing is prior peer review. In prior peer review, articles are not published until they pass muster with a small group of experts, usually two to three people. The notion is that these experts will carefully consider the evidence and conclusions presented in any given work, only publishing those works which pass the quality test.

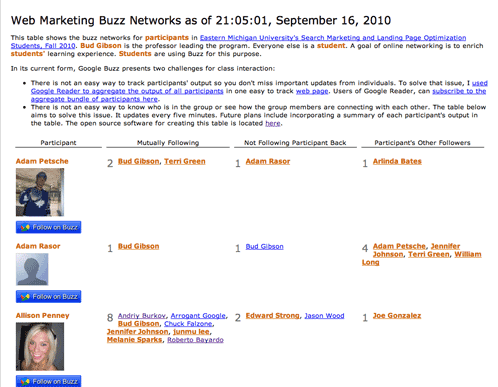

In the remainder of this essay, I'll first outline why prior peer review is the problem not the solution for the dissemination of quality academic research. Then, I'll present one approach I've cobbled together with Google Buzz.

Prior peer review is the problem, not the solution

The problem with prior peer review is that it effectively limits the scope of review to just a few people, some of whom may not be particularly qualified or may be operating on an agenda that precludes publishing certain, otherwise meritorious pieces. Even in prior peer review's most benign form, it implies that work must fit within the current consensus, which tends to change infrequently at best.

I once had an article go through peer review at four separate outlets over the course of a decade before getting accepted for publication.

When I first started trying to get the article published, it was a bit out there. It applied cutting edge statistical techniques to understand the effectiveness of emotion-laden persuasion tactics used by credit collectors. The article is now available for purchase online from a prestigious journal at the single article price of $30. If you're really interested, I'll be happy to send it to you gratis. I didn't do it for the money.

For all ten years this article was under review, its fundamental conclusions did not change, though there were additional analyses performed and re-packagings undertaken. The end result was a piece of writing hidden behind a paywall. In other words, ten years of effort for non-dissemination beyond the journal's subscribers.

Enter Google Buzz

Given this tale, one can reasonably wonder what Google Buzz has to offer. After all, it doesn't seem in any way to match the process I've just described.

When trying to publish your work, there are three things that matter:

In the prior peer review model, the feedback that matters comes from the reviewers prior to any dissemination. Targeting is based on what your colleague's read. Reach is typically limited to those colleagues and their cohort.

Now, consider Google Buzz. For significant efforts, I typically get feedback from 10 or more people. Often a number of people will reshare the post, sending it on to their audiences which often number in the thousands. Some of these individuals alone have greater reach than any, other than the best-known, academic outlets.

But, do any of these Google Buzz people know anything?

To use Buzz effectively, you need to target people who know something. I've basically cultivated Buzz associations based on my intellectual interests. It turns out that these intellectual interests all relate to the extremely applied research agenda I am pursuing in Internet APIs, online social networking, education, and (oddly enough) web marketing. I'm getting feedback from people highly knowledgeable in all of these areas. I suspect this feedback will particularly help me on the software end of the endeavor as well as in understanding some of the implications for online social networking

But is it academic publication?

One thing my Buzz postings clearly are not is dissemination to a small group of experts after approval by an even smaller group of experts. In that sense, they are not academic publication.

However, it's important to remember that academic publication started out as the exchange of letters between people who thought they could profit from talking to each other about the work they were engaged in. I'm essentially using buzz as the envelope for a similar endeavor.

I would describe the buzz posts I've worked on and crafted for feedback as having achieved the kind of engagement I wanted: specifically feedback from highly knowledgeable people who, in some cases, have built significant businesses using the tools and social networking phenomena I'm investigating. Two recent examples of posts that illustrate this dynamic are: the distribution of friend connections among Buzz users relative to Facebook users, and how to infer a person's online social connections even if they keep them private.

So, my personal answer is that Google Buzz is providing me a platform for more engaged academic publishing than what I achieved through the more traditional route.

What's the long term prognosis?

To a large extent, the importance of what you do depends on how it impacts others. I'm doing everything I can to have impact, and enlisting knowledgeable input from others strikes me as important in achieving that.

I'm somewhat less concerned by the sociology of academia. Demonstrating impact tends to trump all.